The opening chapters of The Worst Journey in the World span half the globe, but the main location is always the same: the barque-rigged whaler with auxiliary steam, christened Terra Nova when she was built for the Newfoundland oil trade in 1884. When Capt. Scott bought her for the expedition, he registered her as a private vessel with the Royal Yacht Squadron, so her formal name during her Antarctic career is Terra Nova RYS.

I needed to know my way around her intimately in order to draw the graphic novel. To help me with this, I brought together historical photo reference and some surviving ships, primarily the Star of India in San Diego and the RRS Discovery in Dundee. I hope the following tour with help you get your bearings.

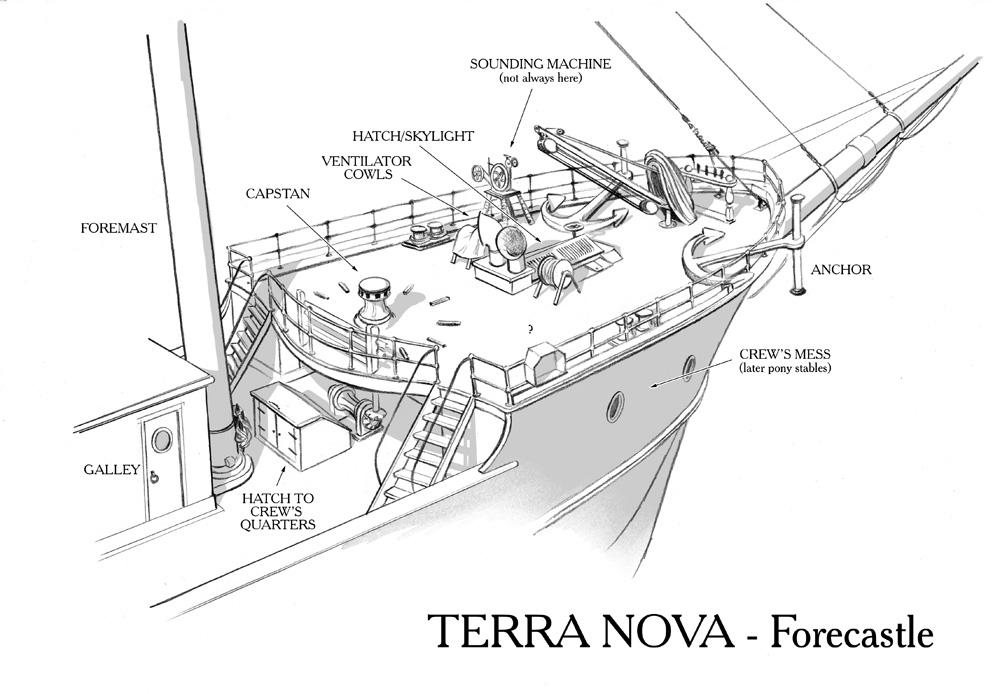

The Forecastle (Fo’c’sle)

Galley – The ship’s kitchen. The Terra Nova was known for rolling heavily in a swell, which gave rise to the saying “A moderate roll rings the bell; a big roll brings out the cook” when poor Archer would be tipped out the door.

Capstan – A sort of winch for winding up the anchor chains, or whatever else needed winding. The square holes around the top would have a long wooden arms fitted in, and several men would push these round to wind whatever. (These handles are stored on a rack behind the rail in my drawing, but in most photos they seem to be strewn at its base.)

Ventilator and skylight – The area below deck, here, was the crew’s mess (common/dining area) for most of the journey out, but when they arrived in New Zealand it got converted into stables for 15 of the 19 ponies, and the crew ate in their sleeping quarters on the deck below. Whether full of seamen or horses, some air flow would have been much appreciated.

Sounding Machine – Usually operated by Lt. Rennick, it was a means of finding out how far down the ocean floor was and what it was made of. Aside from the scientific interest of this, it was an important geographical tool, as depth maps could tell you roughly where you were in places that had been well surveyed, and could alert you to underwater hazards. During the Antarctic winter, the Terra Nova was employed taking soundings for a dangerous and unmapped area around the northern tip of New Zealand.

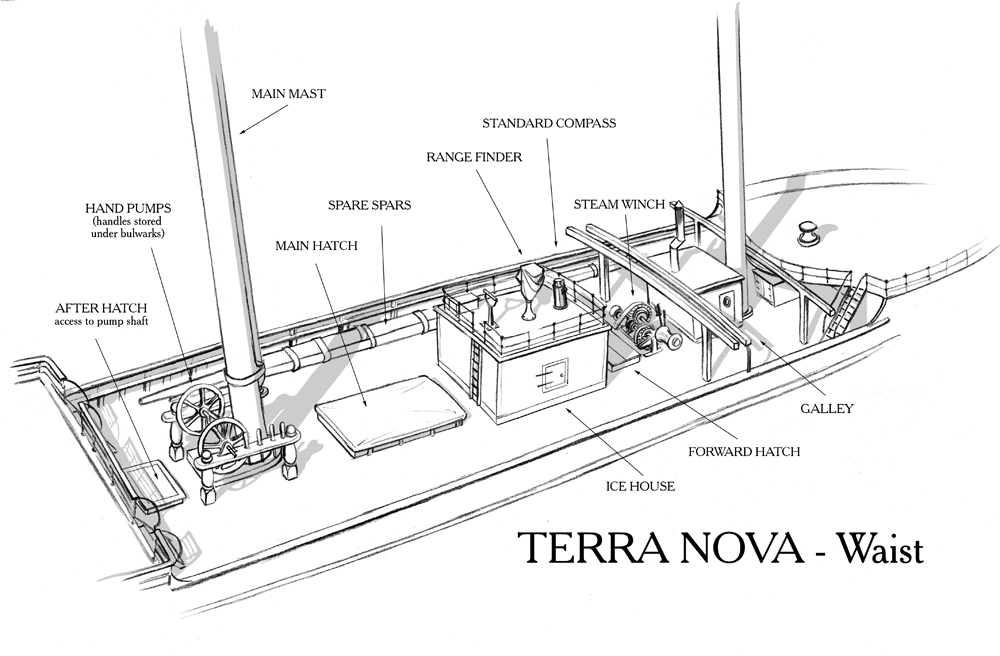

The Waist

Ice House: Basically a giant cooler, the ice house served other purposes as well: In the tropics, Bill and Cherry (and frequently several others) slept on it, as the cabins were stifling, and in the great storm south of New Zealand the dogs got moved here so as not to be swept overboard.

After hatch – In the great storm, the pumps clogged. The only way to get into the pump shaft to clear them out was through the after hatch, but the seas regularly washing the ship made this a very bad idea. See The Pumps for what they did about this.

Main Hatch: The largest access point to the hold, where cargo and coal were stored. Birdie Bowers fell through this, nineteen feet to the bottom of the hold, while the ship was being refitted in London, and brushed it off. On their way to Antarctica, two of the three motor sledges, in their great wooden crates, were stowed either side of the main hatch.

Range finder: Placed on top of the ice house for visibility, this was used to ascertain the distance to landmarks for the purposes of surveying, and was in regular use along Antarctic coastlines.

Steam winch (forward): This may have been used to load coal and other cargo when the ship was in port, but I have not found any mention of its use. It would have been a key utility of the Terra Nova when she was working as a whaler.

Forward hatch: On the way south from New Zealand, the ponies which didn’t fit in the forecastle stables were housed here, between the ice house and the galley. Although they were more exposed, they fared better than the forecastle ponies in the storm.

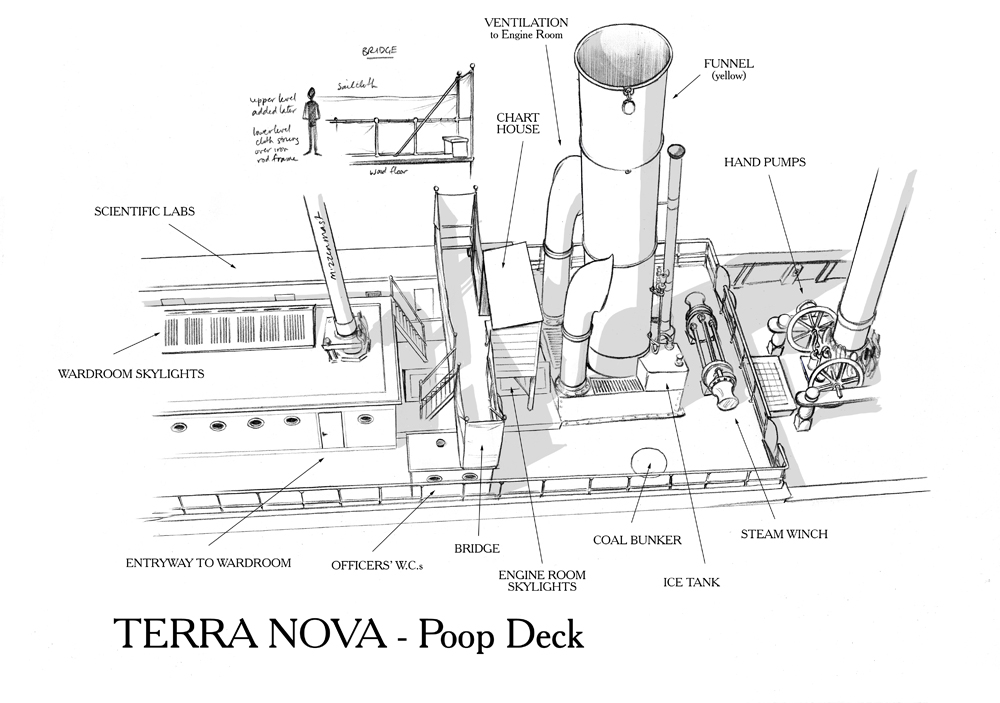

The Poop Deck

Technically, everything aft of the waist is the poop deck, which comes from the French poupe for ‘stern’. But it’s too big for one illustration, so I broke it in two; this, and the stern.

Wardroom: The officers’ mess, where they ate and worked. This was actually on the deck below what you see here: immediately in from the door was a steep stairway down. On the opposite side of the mizzen mast from us was the chart room, an enclosed version of the structure you see in the middle of the bridge. Pennell would do his navigation calculations in there, and if the man at the wheel wasn’t concentrating he’d dash out within a minute to demand why they were off course.

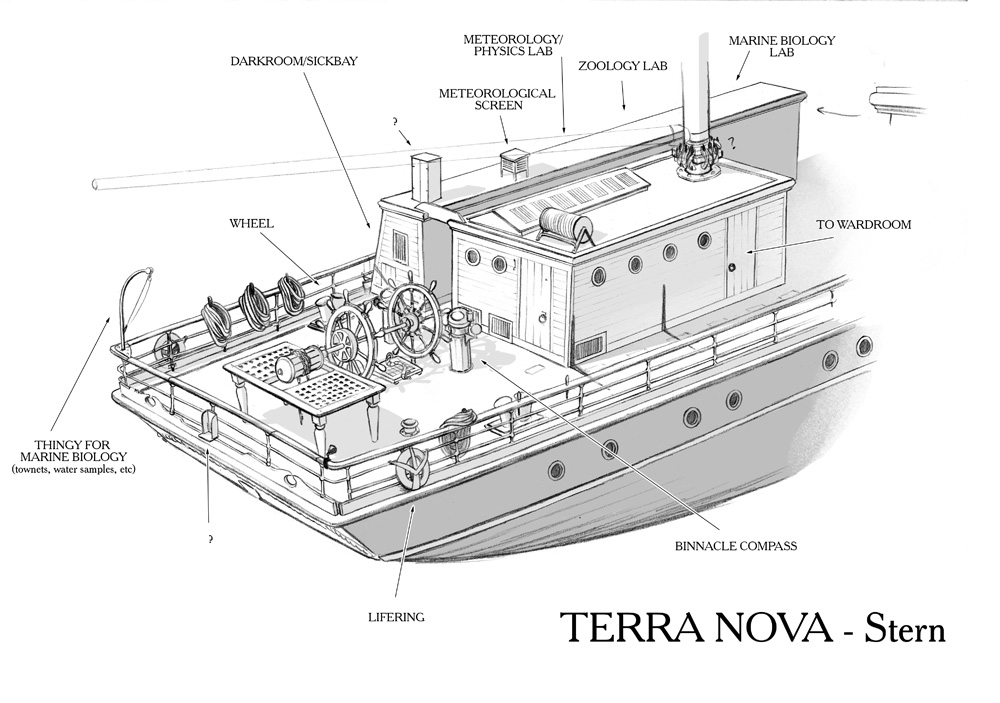

Scientific labs: These were specially built for the expedition, and are detailed under The Stern. As far as I know, there are no photos of their interiors, but all accounts have them crammed full of equipment and instruments.

The Bridge: The command centre of the ship, from which orders would be given. It has maximum visibility in all directions. I think the upper tier of canvas was only added after leaving New Zealand, to keep off the biting wind.

Chart house: Where the navigator could spread his maps, with a little shelter from wind and water. Pennell had a bunk in one of the officers’ cabins, but slept under the table here in all weathers. To my chagrin, I learned after finishing Vol.1 that the roof actually slanted the other way.

Steam winch (aft): This second, larger steam winch was taken out in New Zealand and one of the motor sledges stowed in its place.

Coal bunker: Actually the hatch to said bunker, which is a box built into the ship with an outlet to the engine room where the stoker would shovel coal into the furnaces. Quite a lot of the work for an off-duty sailor was moving coal from one of the holds into a bunker so the stoker could use it.

Ice tanks: Once they reached the pack ice, they harvested freshwater ice to place in these metal boxes around the funnel, where the heat from the exhaust melted it into drinking water. The Terra Nova had been short of fresh water for most of the journey: they didn’t load any in Madeira for fear of typhoid, and from New Zealand three of the four water tanks were full of horse fodder.

The Stern

From this angle you can see the other door to the wardroom, which opens onto the aft end of the balcony. It must have been closed during the storm, but it’s open in every photo I’ve seen.

Binnacle compass: A large floating compass mounted on a column near the wheel, which the helmsman would use to steer. This would be cross-checked frequently with the standard compass on the ice house, which was calibrated to compensate for how the iron in the ship influenced the magnetic field.

Thingy For Marine Biology: This is called a davit when used to hold up the boats, but I don’t know if the name holds when it’s repurposed for plankton-catching tow nets and ocean water sampling.

Darkroom: Only ever intended to be a darkroom, and built as such, but photographer Ponting didn’t join until New Zealand and Lillie got measles well before that, so he got quarantined in there. It served as sickbay again after Ponting joined, for he was a poor sailor and spent the duration of the storm horrendously seasick.

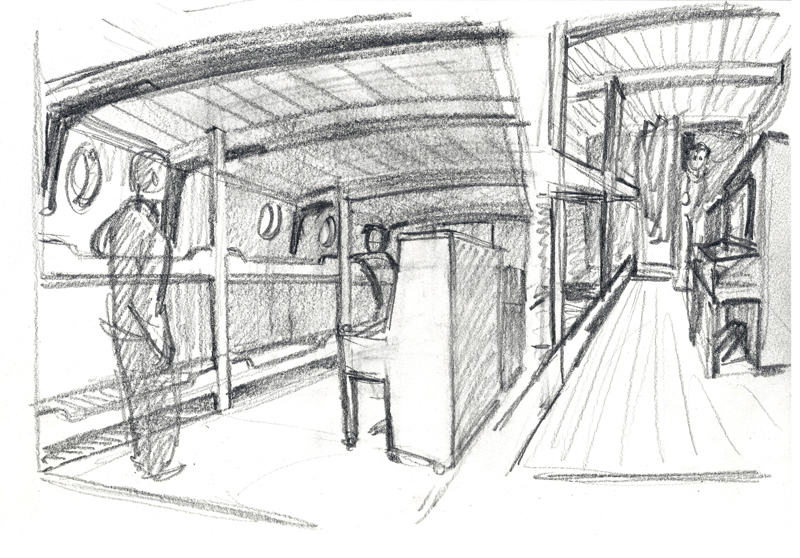

The Wardroom

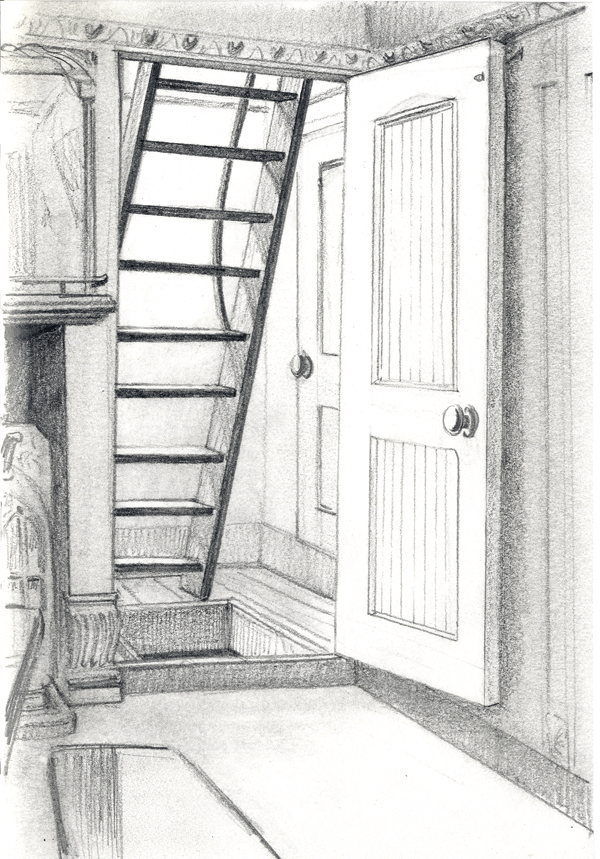

The ship is divided in two: the seamen (or ‘men’) live forward, and the officers aft. On the Terra Nova the officers are collectively known as The Afterguard for this reason. Their headquarters was the wardroom, a large common area under the poop deck at the stern, from which they accessed their cabins. There are only three extant photos of the Terra Nova below decks, and all three are of exactly the same angle in the wardroom. This is the corresponding view in the wardroom of the Discovery:

The Terra Nova was a humble whaler rather than a purpose-built government research ship, so she had whitewash instead of polished mahogany, but the size and layout was almost the same. When I made my research trip to the Discovery, I could sit at the table and project what the Terra Nova would have looked like onto what I was seeing there.

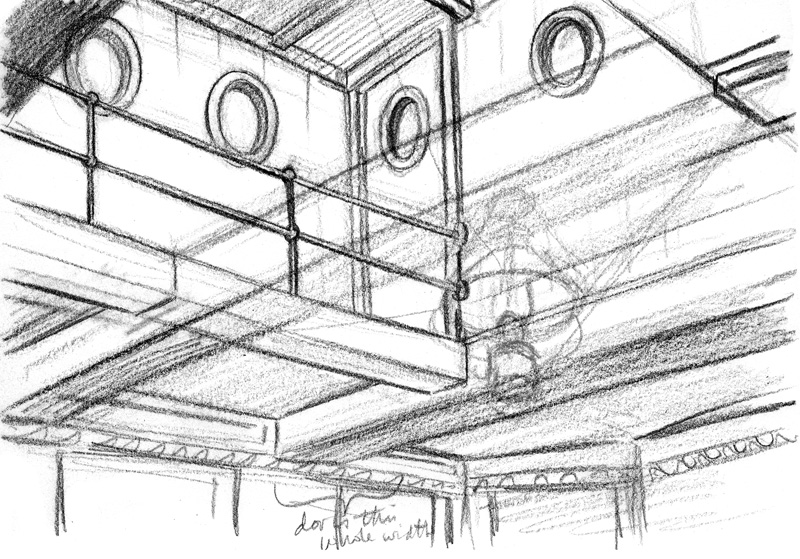

The Terra Nova‘s wardroom skylight had been raised and a deckhouse built around it, giving the wardroom a sort of second storey. Along the starboard side of this ran a balcony, with a door to the quarterdeck, and another at the forward end of the deckhouse, on the starboard side. This balcony was handy as a sort of mudroom for those coming in with wet oilskins and icy clothing, to change before heading into the dry comfort of the wardroom and cabins.

In the aforementioned three photos of the Terra Nova‘s wardroom, there’s a companionway visible outside the door which is to the right in the Discovery photo above. This led to up the door on the starboard side of the deckhouse. When one came down the steps, there was a hatch to the lazarette immediately beneath – ideally, if it were open, there would be an iron bar blocking you from accidentally stepping into it, but it was so commonly left open that people got accustomed to feeling their way around it, and this bar was hardly ever put in place. I’d read several descriptions of this, but had trouble picturing the configuration in my head; seeing the corresponding hatch in the Discovery slotted everything into place.

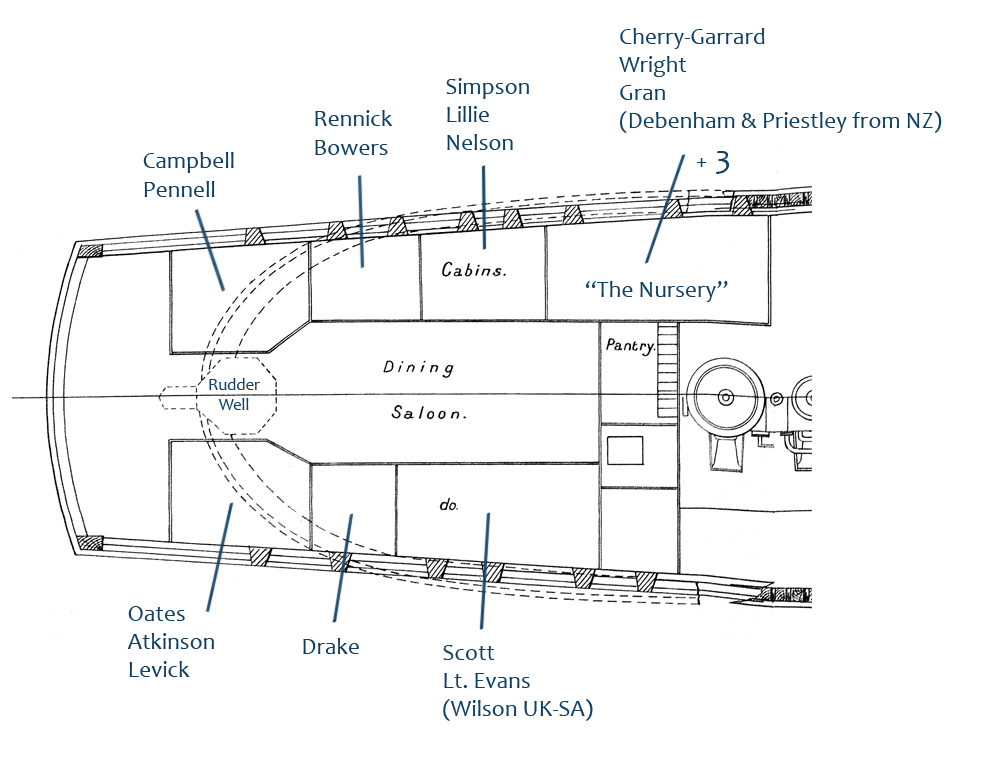

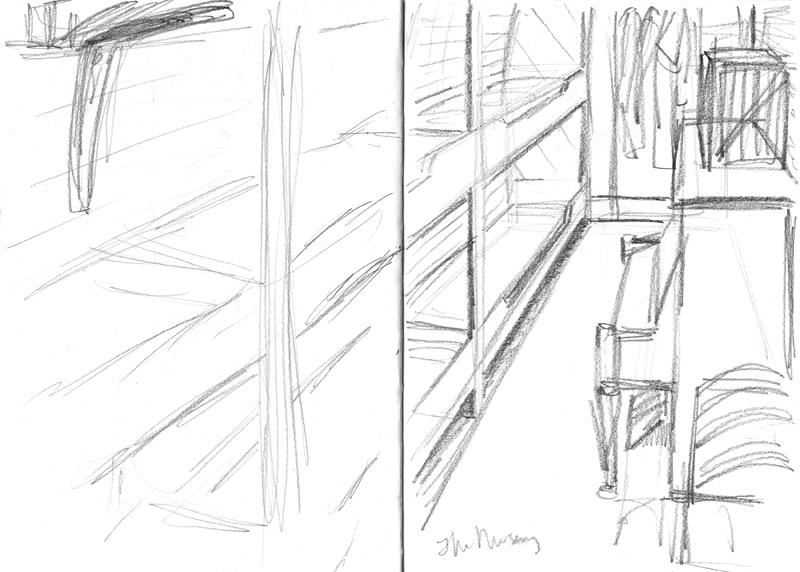

The Nursery

The officers’ cabins opened off the wardroom. These were nearly all shared with at least one other person; even Capt. Scott didn’t get his own personal space. Cherry lists the cabins’ occupants thus:

The cabin of most interest to our story is The Nursery, so named because the most junior officers were housed there, along with a decent amount of cargo.

There are fifteen officers here on board, including scientific staff. In my cabin (The Nursery) there are four of us. [This was written on leaving Cardiff.] The cabin is 15′ long and almost 6′ wide and contains in addition, the pianola, the library and about five hundred or more rolls for the pianola.

‘Silas’ Wright, quoted in “Silas: The Antarctic Diaries and Memoir of Charles S. Wright” p.8)

The cabin had originally been built as the engineers’ mess. It had a second door that opened onto an engine room catwalk, which was convenient for an engineer, but made the Nursery a sauna when the ship was steaming through the tropics.

I know there were three sets of double bunks, and my best guess was that they were all along the hull wall. Again based on some roughly similar spaces on the Discovery, and descriptions in journals, this is how I figured it may have looked:

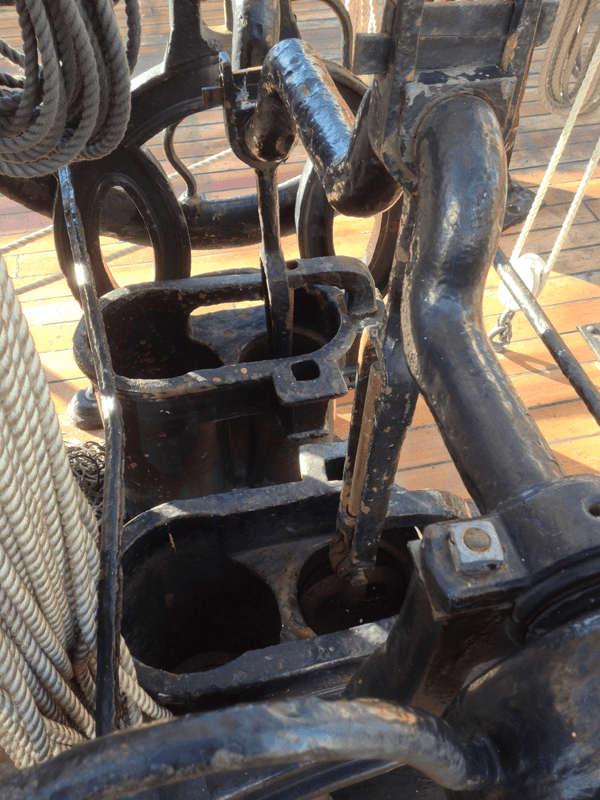

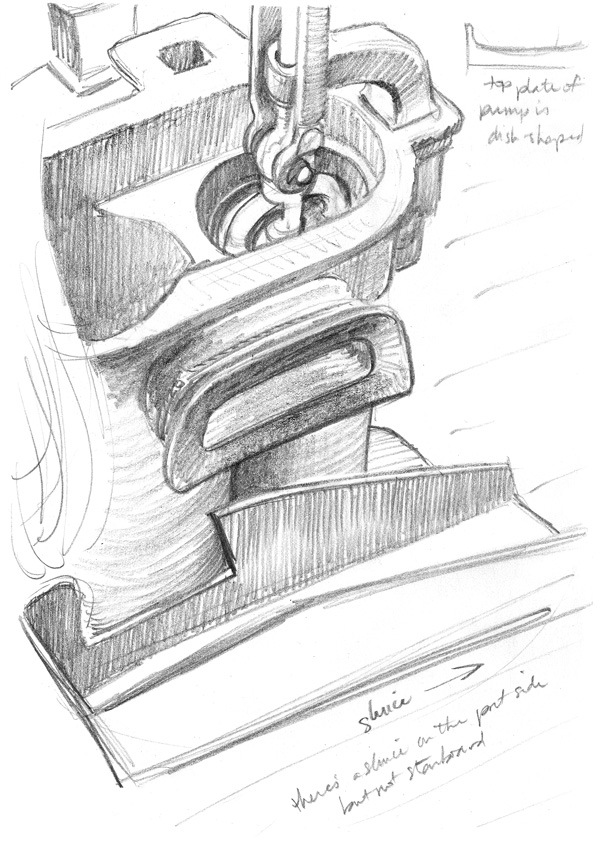

The Pumps

The Terra Nova was a wooden ship, and wooden ships naturally leak a little. When sailing, pumping out the bilges is one of the regular ship’s chores. However, the Terra Nova took in far more water than usual, and the crew spent an inordinate amount of time on the pumps.

From first to last these pumps were a source of much exercise and hearty curse . . .

The Worst Journey in the World, p.27

Once they reached New Zealand and they had time and resources to drydock the ship, they found the source of the leak: During the refit in London, someone had drilled a hole for a bolt in the stern, which had failed; they drilled a new hole and left the old one unplugged. So many hours’ labour for an inch-wide oversight.

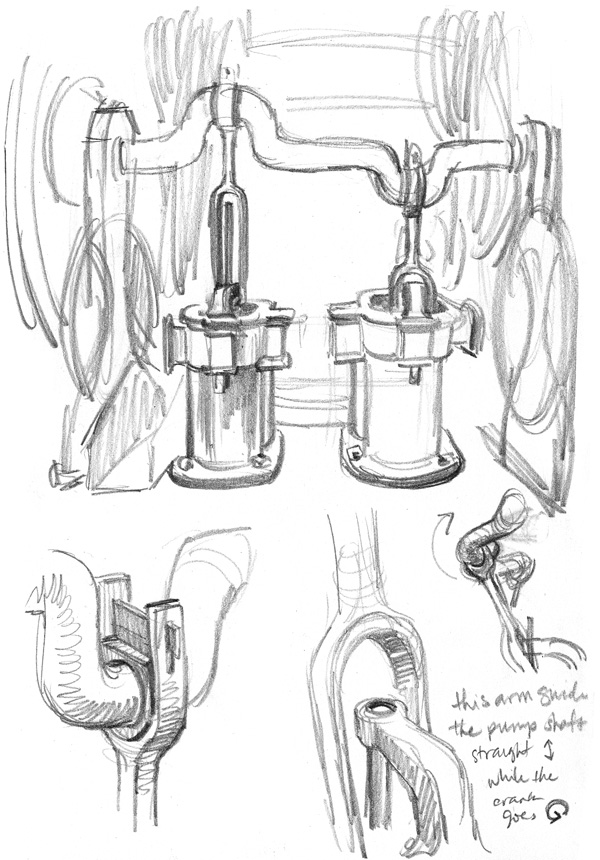

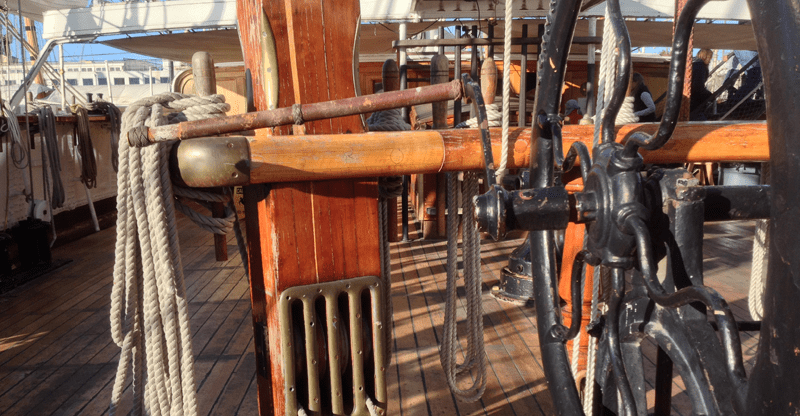

For being such a significant part of the story, the Terra Nova‘s pumps are not very well documented, so I based mine predominantly on the pumps of the Star of India, which is twenty years older, but built in the same tradition.

The Star of India‘s pump handles are sized for two men; the Terra Nova‘s were initially for four, but in South Africa she was refitted with handles that spanned the deck and mounted into the bulwark, which could accommodate six men pumping. When not in use, these were detached and stowed to the side.

Besides the leak, the burdened pumpers of the Terra Nova had another complication to deal with:

As we found later, some never-to-be-sufficiently-cursed stevedore had left one of the bottom boards only half-fitted into its neighbours. In consequence the coal dust and small pieces of coal, which was stowed in this hold, found their way into the bilges. Forty gallons of oil [which had got loose in rough seas in the South Atlantic] completed the havoc and the pumps would gradually get more and more clogged until it was necessary to send for Davies, the carpenter, to take parts of them to pieces and clear out the oily coal balls which had stopped them.

The Worst Journey in the World, p.27

These coal balls led to one of the most exciting feats of derring-do during the almighty storm which threatened to sink the Terra Nova on her way south from New Zealand. Because the deck was continually awash, they couldn’t open the hatch from which the pump shaft was accessed, so they had to chisel a hole through an iron bulkhead from the engine room into the coal bunker, and hack into the pump shaft from the side. Then Teddy Evans and Birdie Bowers (the smallest crew members) took turns climbing down it and clearing the pump intakes by hand.

The Star of India’s pump pipes are exposed, rather than encased in a shaft, but you can imagine what a cramped job it was if you picture these encased in a wooden cylinder than only just fits.

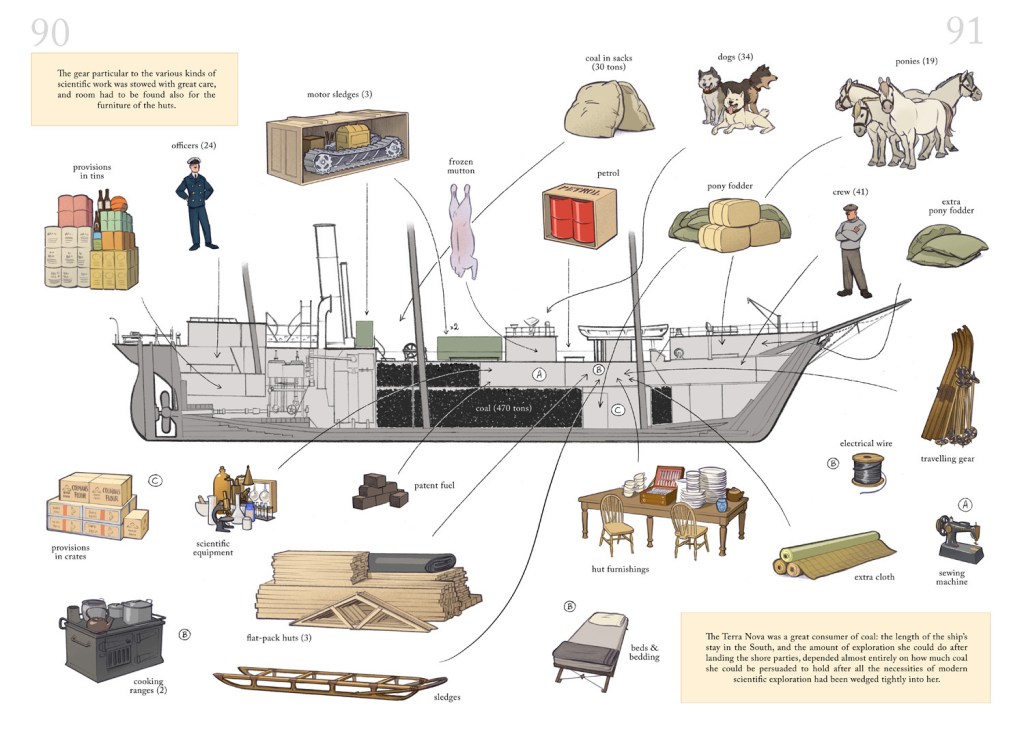

Loading the Terra Nova

My sources for how the Terra Nova was loaded on departing from New Zealand are Scott and Bowers; they generally agree, but as Bowers was in charge of stores, I default to him when they don’t. I sat down with the written catalogue and the plan of the ship, and figured out this diagram for the graphic novel:

Alas, the Terra Nova is no more – she was sunk in the 1940s off the coast of Greenland after getting the worst of some ice, and is now just a patch of sludge on the ocean floor. I hope my work reconciling photos with descriptions and surviving ships has brought her back to life in some small way. After so long walking her decks in my head, it’ll be hard to say goodbye at the start of Vol.2 … but then I get to draw Antarctica instead!

Everything on this page originated in posts on my Patreon, which I shared with my supporters throughout the research phase. The detail is more exhaustive over there, so if you’re still curious, sign up and dig into the Terra Nova tag. You can also tumble a 3D model of the ship, thanks to Daniela Schaffenberg and her ability to translate Edwardian diagrams and my sketches into geometry.